How many times have you heard or said sentences like “I learned French in school”, “I would like to improve my Spanish” or “I am taking Arabic classes”?

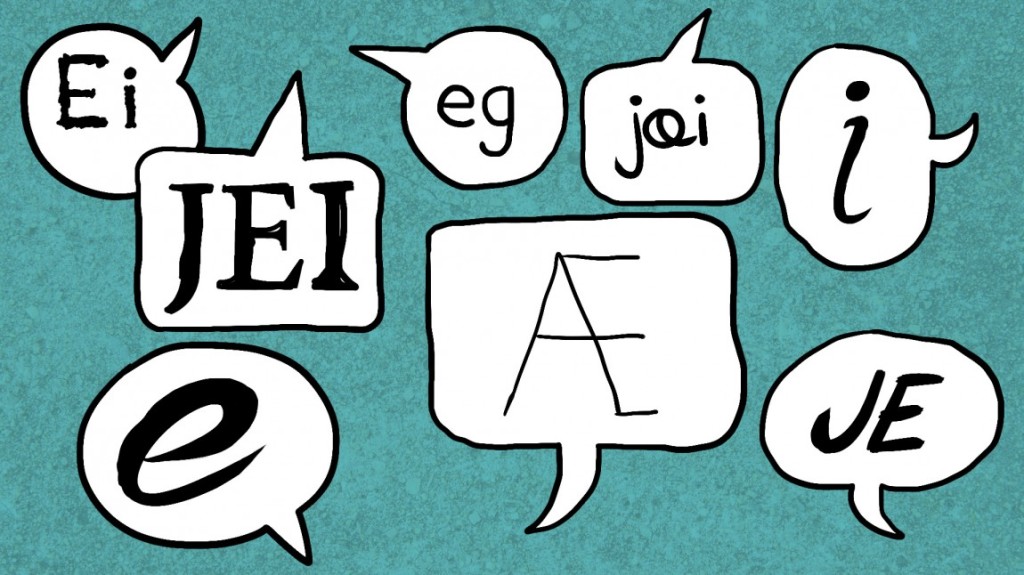

And how many times have you actually asked or been asked the question that would linguistically be most evident and appropriate as a follow-up: “Which French?”, “Which Spanish?” or “Which Arabic?”

Unless a specific context makes us aware of the differences within what we call “a language”, we refer to “languages” as if they were easily separable and countable entities. Looking at it from a linguistic point of view, reality is not that simple.

Of course also non-linguists know that there are variations in every language we know. But what exactly is a “language variety”?

Hoffmann (see: sources) distinguishes between six different types of language variety: the ways of speaking (or writing) of different social groups (Soziolekt), professional fields (Professiolekt), fields of communication (Funktiolekt), regions (Regiolekt), social situations or styles (Emotiolekt) and media of communication (Mediolekt). The one that we are probably most aware of in our daily communication is what is commonly referred to as “dialect” – the language varieties that people from different “regions” speak. Those varieties can refer to small regions such as “Northern Luxembourgish” or “Swiss German” or to vast parts of the world such as “Indian English” or even “African French”. They can be officially recognized and valued national languages with distinct written standards like “Austrian German” or inofficial oral varieties that are neither recognized as “proper language” nor possess any particular value outside their speech communities like “Styrian German” (the variety spoken in the Austrian state of Styria responsible for Arnold Schwarzenegger’s unique accent in English).

For languages that are widespread and spoken in many different places across the globe there are of course often a lot of well-known regional varieties, but in fact every “language” consists of many varieties. This is because what we usually refer to as “standard language” is a norm invented for the purpose of the formation of nation-states not more than 200 years ago, and does not actually exist in the reality of our speech. Language is constantly changing and adapting to the people speaking it and the things they need to name and express, or as Weber and Horner (see: sources) put it: “Spoken language is something living that ultimately cannot be fixed”. There are not two people on this planet who speak exactly the same way, which is why any “standard language” can never be more than a least common denominator – even in a speech community who believes that it speaks exactly according to its written standard.

If you have ever tried to learn or teach a language, you will know that this “standard” however plays a crucial role for most people in this context. Of course there are many people who learn a language by immersing themselves into a certain language community – be it by listening to people, reading magazines or trying to communicate with other speakers. This type of learning seems to not necessarily require an explicit “standard”. But as soon as you add someone taking the role of a teacher – however informal this may be – the situation changes. As a matter of fact, the teacher will have some rules and norms in mind (which do not even need to be conscious) that s/he refers to when explaining, giving examples or correcting the learner’s speech.

Teaching often requires a certain reduction, generalization and abstraction of language. This level of simplification is crucial to help learners with understanding, processing and memorizing. Good language teachers therefore need rules, norms, prescription and correction – short: a certain commitment to the “standard language”.

For languages that are widespread and spoken in many different places across the globe there are of course often a lot of well-known regional varieties, but in fact every “language” consists of many varieties.

But there is another element that is absolutely crucial for good language teaching: keeping in mind the real world’s people’s language use and its complexity and awareness that what students read in their British English exercise book is not necessarily what they will hear on the streets in Sydney. For English this sounds like a very obvious example. But how aware are we of this situation for other languages? How aware are we that what students read in their French exercise book is not necessarily what they will hear on the streets in Togo or what students read in their German exercise book is not necessarily what they will hear on the streets in the German part of Belgium?

Awareness of and reflection on linguistic varieties are absolutely crucial for every language teacher – in school as well as in second and foreign language teaching. But how do you decide which variety to teach? In his handbook for English teachers – a classic for teacher training courses – Scrivener (see: sources) dedicates a section to “Choosing which variety of English to teach” and answers the question of which variety to teach with a clear “There is no simple answer”. To find the answer he suggests asking yourself some more questions. The first and most important one being: “Which variety do the learners need and expect?”

This is the point where learners need to get actively engaged. When learning a language, it is essential to think about the possible context(s) you will need this language for. Because nothing is more frustrating than studying a language for years and finally going out on the streets and not understanding anything because the “standard” variety you were studying was too different from the regional or social variety you actually need.

So, dear language teachers: ask your students about the varieties they might need and about the regional, social or professional contexts they are learning “the language” for. Even if they answer with varieties you are not able to teach, there are still plenty of things you can do: read about the varieties your students need and familiarize yourself with the most important differences to the variety you are teaching, tell students about those differences whenever it seems helpful, raise awareness which “standard” you are teaching and that this is not the only “correct” variety of this language, record or invite speakers of different varieties to your class or provide texts in a different written standard. And even if your students only need “the standard”, getting a glimpse into other forms of the language is a great contribution to their language awareness.

When learning a language, it is essential to think about the possible context(s) you will need this language for. Because nothing is more frustrating than studying a language for years and finally going out on the streets and not understanding anything because the “standard” variety you were studying was too different from the regional or social variety you actually need.

Finally, dear language learners: Do not just go to any course in “the language” and expect to be taught the one and only standard to understand the whole “language”. If possible, find a course or a teacher to help you with the varieties you want to learn. If not possible, tell your teacher anyway! S/he might have some ideas about how to help you with a specific variety or at least some suggestions about where to look for material. And most importantly: stay aware that the “standard” you are learning is only one variety among many, that it can never be the ultimate truth and that there are always differences between French and French, Spanish and Spanish, Arabic and Arabic.

Written by Olivia Bantan, Terminology Student Visitor at TermCoord – German Teacher & Student at the University of Luxembourg

Sources:

- Hoffmann’s model of different types of varieties: “Ein Modell des Varietätenraums” (Hoffmann, Michael (2007): Funktionale Varietäten des Deutschen, p.6)

- What is a language: Consequences for teaching (Weber, Jean-Jacques & Horner, Kristine (2012): Introducing Multilingualism – A social approach, p.33)

- Choosing which variety of English to teach (Scrivener, Jim (2011): Learning Teaching – The Essential Guide to English Language Teaching / 3rd edition, p.120)

- Image Speech Bubbles: “Norges verste dialekt på pollen nederst i saken” (Mattis Folkestad, NRK P3)