Sometimes we come across words which have cultural references. We do not understand their origins, but we use them anyway. Sometimes these words are referred to as realia – those cultural words which represent a different cultural reality. Examples: sensei, cream tea, arrondissement, tsunami.

Sometimes we come across words which have cultural references. We do not understand their origins, but we use them anyway. Sometimes these words are referred to as realia – those cultural words which represent a different cultural reality. Examples: sensei, cream tea, arrondissement, tsunami.

This post, however, is not about realia but about the ‘other’ cultural words or expression. The ones which have race-related stereotypical connotations if we dig deeper into their origin. Here is a sample from five languages:

Chinese Whispers (UK English) – Definition: a game in which a message is passed on in whispers, where the final version is often radically changed from the original; any situation where information is passed on becoming distorted in the process. Also known as Telephone (US). Perhaps you think Chinese Whispers came from some Chinese historical tradition or it’s a game imported from China? Historically, the very word Chinese denote “confusion”, “incomprehensibility”, “impenetrability”, in short, inaccessible to the Western mind (Dale, 2004). The term for the game therefore came from the assumption that the distorted whispers are as incomprehensible as Chinese. The French adapted this to their colonial past by calling it le téléphone arabe.

Arabe du coin (French) – Definition: A corner shop often owned by a north-African which opens late-nights and weekends. Presumably, these shops are all owned by “Arabs” (the word itself is a generalisation). In the UK, this can be translated as a Paki shop (very offensive). Also known as dépanneurs (Quebec French).

鬼佬 Guǐlǎo (Cantonese) – Definition: A foreigner (in particular a westerner). Gui means “ghost”, and lao means “guy”. Historically, this is perhaps due to the pale skin colours of westerners which is associated with ghosts. Also known as 洋鬼子 yángguǐzi or the modern, less offensive version 老外 lǎowài(Mandarin). Guilao was used during the opium wars to express hatred and negativity against the British invaders, as well as during the Japanese occupation in Hong Kong in the Second World War. Nowadays, though it is considered derogatory by some, Cantonese users do not see it as derogatory (or it’s not used as such). Some foreign settlers even embrace the term. Derivatives: 鬼婆 guǐpó “a non-Chinese woman”, 白鬼 báiguǐ “a white person”, 黑鬼 hēiguǐ “a black person”.

Fare il portoghese (Italian) – Definition: Someone who doesn’t pay, a leech (literal translation: to act like a Portuguese person). Although this term sounds like a racial stereotype, it is actually derived from when during the 18th century, the Portuguese ambassador visited the Vatican. He invited all Portuguese people in Rome to attend a play at the theatre for free if they only declared they were Portuguese at the entrance. So many Romans took the opportunity to fare “pretend” to be Portuguese in order to get in for free.

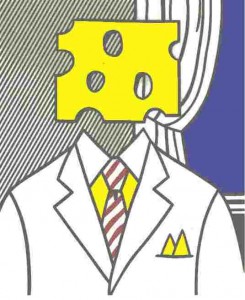

Käsekopf / Kaaskop (German/ Dutch) – Definition: traditionally a wooden cup-shaped form (spherical) where Edam cheese is pressed. Also used to refer to a Dutch person (literally: a cheese head) by the Dutch ex-colonies such as South Africa, by neigbhours such as Flanders, as well as Germans with the negative connotation of a “dummy” or a “stupid person”. Most people presume this comes from a stereotype that Dutch people eat a lot cheese.

The list can go on. Just as all languages have swear words, so all languages have words and expressions with ethnic slurs that reflect a certain racial stereotype. This is not to say that a particular language is more “racist”. Indeed, language use reflects on the individual speaker’s views more than the country or the language itself. Where there is a will, there’s a way as the saying goes. The aim of this article is not to attack or reflect badly on particular languages; rather the aim is to make users aware of their own language etymology and how historical events play a part. Like history, we must not repeat the mistakes, but learn from them.

Recommended Reading: Dale, Corinne H., (2004). Chinese Aesthetics and Literature: A Reader. New York: SUNY Press.

Article written by Jiayi HUANG, current trainee at TermCoord.