Sicilian cassata as we know it today has nothing to do with the culinary saying “the simpler the better”. This tempting Baroque cake, which is prepared only in a few households as the majority prefers to leave it to the skilled hands of experienced confectioners, owes its existence to the millennial foreign dominations that have weaved Sicilian history.

The origins of the word cassata spread through alternating phases of colonization and fruitful blends of cultures and traditions, and are blurred by oral transmission and an irresistible legendary flavour. Its etymological derivation has been originally traced back to the 9th-century Arab occupation of Sicily; more precisely, to the word qas’at that referred to the round pan used to shape a cake made of ricotta cheese and sugar. Other sources attribute the derivation to the word quesada, a Spanish designation for Catalan culinary specialities made of cheese, coming directly from caseus, the Latin for cheese. Since the Arabs began their occupation centuries before the Spanish dynasties, it seems likely that the word cassata has Arabic roots while over the centuries it began to incorporate also Spanish influences.

This intermingle is also reflected in its recipe. Originally, as confirmed by the Sicilian-Italian dictionary by Mortillaro Vincenzo published in 1853, cassata was a rather simple pastry made of dough stuffed with sugared ricotta cheese and, occasionally, with candied fruit and chocolate chips. This constitutes what is nowadays called cassata al forno, baked cassata. The dough is made of pasta frolla crust, an Italian kind of pie dough, which is simpler to obtain and explains why most Sicilians prefer this al forno version to the homemade variant. However, as pastry making and wealth increased in the island, aged nuns replaced the old Arab recipe with a surface and side decoration made of pasta martorana, a marzipan obtained from the mixture of almond flour and sugar, eventually green-coloured with herbal extracts. In the following centuries, the Spaniards brought to Sicily the recipe of the so-called pan di spagna, sponge cake, while sugar icing and elaborate coloured decorations of marzipan were sprinkled during the Baroque age. This gradually came to form the uncooked version of cassata that is currently served in restaurants and sold in almost every Sicilian confectionery.

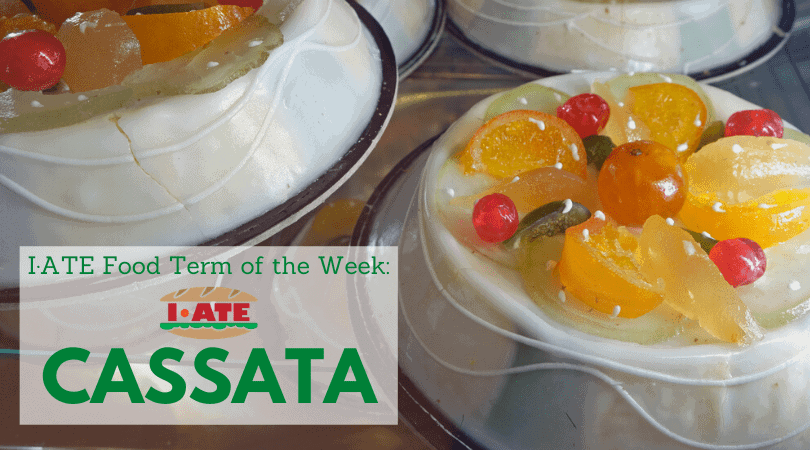

Even if in past times this delicacy was the delight of Easter festivities, today this magnificence of layered liqueur-soaked sponge cake and sweetened ricotta cheese, candied fruit and chocolate, surrounded by green marzipan and decorated with garnishes of marzipan fruits and flowers, can be found all the year around. Among many other elements, cassata also testified to the closeness and prosperity of the two monotheistic religions in the island: indeed, historical documents show the cake was made by both nuns for Easter and Sicilian Jews for Purim. There is also a 16th-century veto from the city of Mazara del Vallo prohibiting its making at the monastery during the Holy Week because the nuns preferred to bake and eat cassata than pray. From its simplest version to the latter, more elaborate and solemn, cassata is believed to encompass the inner Sicilian soul that roams freely from the goodness of humble origins and genuine raw ingredients to the refinement of Baroque intricacy.

As with all preparations that carry the same name through time, there is no doubt that cassata became different things in different eras and places. Within Sicily, apart from the distinction between the two variants, cassatelle di Sant’Agata are small dome-shaped cakes that imitate St. Agata’s breasts: this individually-sized cake is a tribute to the martyrdom of the Saint, who is the patron of the Eastern city of Catania.

In recent times Sicilian cassata has inspired many curious re-adaptations. In the US, Italians who immigrated at the turn of the 20th century spawned a whole new variety of cassata, from versions spiked with chocolate and coffee to some – like the fruity one popular in Cleveland – made without ricotta cheese. In Australia, cassata is an ice confectionery sold in individual portions; it resembles the Neapolitan re-interpretation of the Sicilian cassata for its small shape and its colours: pink, green and white, this ice cake is made of a pink layer in the centre obtained through soaking and flavouring with a cherry liqueur, and two layers sprinkled with candied-fruit.

Whichever version of the cassata has sparkled your curiosity, make sure a taste of this twisting and sweet history rests in your mouth and sates your appetite.

Sources:

Mortillaro, Vincenzo. (1853). Nuovo Dizionario siciliano-italiano. Palermo: Stamperia di Pietro Pensante.

De Gregorio, G. and Seybold, Chr. F. (1903). “Glossario delle voci siciliane di origine araba.” Studi glottologici italiani. Vol. III.

Ahmad, Aziz. (1975). “A History of Islamic Sicily”. Islamic Surveys, 10. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Clifford A. Wright (1999). A Mediterranean Feast: The Story of the Birth of the Celebrated Cuisines of the Mediterranean from the Merchants of Venice to the Barbary Corsairs, with More than 500 Recipes. William Morrow Cookbooks.

http://www.bestofsicily.com/mag/art203.htm.

http://www.cliffordawright.com/caw/food/entries/display.php/topic_id/13/id/119/.

https://www.lacucinaitaliana.it/storie/piatti-tipici/storia-e-origini-della-cassata-siciliana/.

Carmen Serena Santonocito obtained her PhD at Università degli Studi di Napoli “Parthenope”. Her research interests range from critical discourse analysis to gender studies and the discourse of novel and organic food.