The increasing exchange of experiences and knowledge between the fields of Natural Language Processing (NLP), Information Retrieval, Corpus Linguistics, Computational Linguistics, Knowledge Engineering and Artificial Intelligence has opened new methodological and applicative perspectives to Terminology.

Terminotics is an interdisciplinary field concerned with the application of Computational Linguistics (computer science applied to the analysis and synthesis of language data) and Linguistic Engineering (creation of NLP resources and tools) to terminographic and terminological tasks.

Therefore ‘Terminotics’ can be considered as a blend word, combining both ‘Terminology’ and ‘Informatics’.

This orientation, which started emerging in the mid-80s, has revolutionized language professionals’ work, leading to an approach based on the analysis of corpora to extract and collect terms.

This new discipline has:

- sped up and automated the research work thanks to terminology extraction tools;

- facilitated terminology management, retrieval, and updating of terminology by creating terminographic databases.

The Department of Translation Technology (TIM) of the University of Geneva offers a graduate course on Terminotics (named Terminotique and held by Ms Donatella Pulitano in French). It provides deep insight into how to use and evaluate available computerized lexicographic and terminology tools and terminology management software.

This course explores three main areas of interest in Terminotics:

- Terminology management

- Terminology extraction

- Terminology verification

Terminology management

Terminology management is carried out with specialized software products designed to gather, manage and access the data of a terminology collection.

These tools are also known as TMS (terminology management systems), and they can serve for different purposes, such as terminology documentation and compilation, information retrieval, thesaurus management, multilingual document generation, and the management of terminological documents, glossaries and termbases.

To work efficiently, a TMS should be compatible with existing word processors and CAT tools and should be able to process and manage an unlimited number of terminology entries. The different fields in a terminology entry should be long enough to integrate all the data (term, synonym, source, context, etc.) without having to truncate them or store them in another field.

Moreover, the software must be able to support language-specific characters and hyperlinks, and a specific field should be reserved for each language. Even if the collection only deals with two languages, it may be useful to have the possibility of integrating equivalents in additional languages. Querying must be easy and based on various search criteria (by field, word combinations, etc.), and it should enable user-friendly and straightforward processing of information.

The choice of a TMS depends on several factors:

- the operating system and the software architecture;

- its intended use and purpose;

- user access levels and rights;

- the number and type of languages to be supported;

- the data to be included in a terminology entry;

- the need to import or exchange data (and formats);

- the need to manage multimedia data;

- the available resources (for the installation of the system and its maintenance).

MultiTerm, TermStar, MultiTrans, Déjà Vu, QTerm, Across and Fusion are examples of TMS available on the market.

Terminology extraction

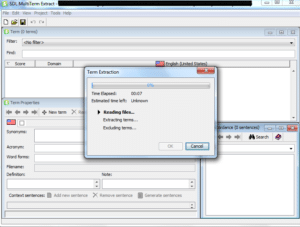

Before moving on to the identification of term candidates, the terminologist must have several resources available, including large corpora which can be monolingual or bilingual. Once the corpus has been assembled, the terminologist can begin with the identification of term candidates, using an automatic system.

A terminology extractor consists of a set of computer programs that attempts to extract terminology units from a computerized corpus. It can be used to extract term candidates, collect useful information for terminological and terminographic work, fill out existing entries and find collocations. However, this type of tool has significant limitations: it generates ‘noise’, that is the retrieval of irrelevant term candidates, and ‘silence’, defined as failing to retrieve relevant term candidates from the database and therefore requires manual intervention.

The extractors can be based either on a statistical or a linguistic approach and can be carried out on monolingual or bilingual corpora. Tools based on the statistical system operate by comparing identical repeated character strings independently of languages and do not require prior lemmatization.

The extraction of term candidates based on a linguistic process usually involves segmentation (tokenization), morphological analysis and lemmatization, labelling and disambiguation and extraction. These tools effectuate a full morphological analysis to identify the lemma for each word and identify word boundaries (punctuation marks, conjugated verbs, etc.), leading to more accurate and convincing results.

The choice of extraction software depends on:

- the format of the documents to be extracted;

- the existence of a list of empty words for the languages concerned;

- the necessary IT infrastructure;

- the need to extract other information in addition to the term candidates;

- available resources.

SDL Extract, Synchro Term and ApSIC Xbench are examples of terms extractors available on the market.

Terminology verification

A terminology verifier is a program or module used to check whether the recommended terminology is used in the source and target documents and aims to detect and report terminological, editorial, and spelling inconsistencies. These tools are essential when (semi-)automating specific processes and can be used before or after the translation or redaction of documents.

During text revision, a verifier tool usually checks for numbers, number formats, dates, formatting, tags, untranslated or copied segments, punctuation, spelling and grammar.

Usually, a terminology verifier can be based on a statistical system or a linguistic system. A statistical system compares character strings and generates a list of the rejected terms and sometimes detects spelling variants or inflected forms. A linguistic system generates a proposal of term candidates, identifying complex patterns of word-formation for each language.

To perform successfully, the verifier must be in the text editor, with Word Add-Ins so that it can tackle terminology inconsistencies at their root. Also, the terminology collection used must include the category ‘normative status’, essential when detecting deprecated terms.

In the end, the verifier tool will produce an annotated text with different colours for each of the problems identified and a summary of the issues, usually contained in a report.

When CAT tools do not integrate the terminology verifier, the language professional may perform a manual revision based on the rules contained in the style guide.

The choice of verification software depends on:

- the format of the documents to be checked;

- the languages to be dealt with;

- the necessary IT infrastructure (including the possibility of interacting with terminology banks);

- the available resources (complexity and configuration of the language systems, preparation of the documents to be checked);

- the need to find term candidates.

Terminotics is essential in the work of “traditional user groups” such as technical translators, interpreters, terminologists, standardization specialists and language planners. Besides them, there are other user groups, like technical writers, subject-field experts, documentation specialists (such as compilers of thesauri), information specialists, and knowledge engineers.

Effective terminology management can impact the speed of translation, the consistency and quality of the target text. It can also help cut costs and facilitate fast turnaround times for translation, which is a pivotal factor in this age of intense market pressures. In the end, the key to success is a complete mastery of these working tools, which undoubtedly have relevant benefits for language professionals.

Sources

Magris M., Musacchio M.T., Rega L., Scarpa F., (2001). Manuale di terminologia. Aspetti teorici, metodologici e applicativi. Hoepli. Milano.

Marzà N. E., (2009). The Specialised Lexicographical Approach: A Step further in Dictionary Making. Peter Lang Publishing. Bern.

Olejnik S., (1999). EUROLOGOS Computerized Translation Technology, [ONLINE], Available at: http://www.francamente2.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Traductique-EN.pdf [Accessed 5 October 2020].

Section de terminologie de la Chancellerie fédérale, (2014). Recommandations relatives à la terminologie, CST – Conférence des Services de traduction des États européens [Accessed 5 October 2020].

Terminotics, [ONLINE], Available at: https://sierterm.es/content/terminotics/?lang=en [Accessed 5 October 2020].

Terminotique, Programme des cours, Université de Genève, Available at: https://wwwi.unige.ch/cursus/programme-des-cours/web/teachings/details/2020-BTM0907?year=2020.

The Department of Translation Technology (TIM), Université de Genève, https://www.unige.ch/fti/en/faculte/departements/dtim/.

Wright S. E., Budin G., (1997). Handbook of Terminology Management. John Benjamins Publishing Company. Amsterdam.

Written by Maria Carmen Staiano, a translation technology enthusiast with experience in project management and localization. She holds a Bachelor’s in Linguistic and Cultural Mediation and a Master’s in Specialized Translation at the University of Naples “L’Orientale”.

Written by Maria Carmen Staiano, a translation technology enthusiast with experience in project management and localization. She holds a Bachelor’s in Linguistic and Cultural Mediation and a Master’s in Specialized Translation at the University of Naples “L’Orientale”.